The opera Ashmedai was written by Josef Tal and Israel Eliraz. It was staged in German at the Hamburg Staatsoper in 1971. The opera raises several cultural-historical questions as it explores the nature of an individual who has lost the capacity for rational judgment. This loss of judgment leads to the distortion of his humanity, as he is swayed by the devil’s false promise to restore a lost paradise to the control of his nation. But the opera is not solely concerned with the individual; rather, it examines the elements that connect an entire nation that abandons its humane values and adopts the reckless ways of anarchy. Breaking free from the burdens of its past gives this nation a new identity and new tools, which allow it to generate progress, wealth, and a new sovereign force. Nevertheless, there are ruinous elements in the nation, which lead its general public to commit acts of murder, rape, and abuse.

The opera tells the story of a king who had ruled with wisdom and maintained peaceful relations with the country’s neighboring kingdoms. In a moment of weakness, the King forms an alliance with the devil, abandons his throne, and chooses to live with his beloved, an innkeeper. Ashmedai (the devil) takes over the kingdom and convinces the King’s son and the kingdom’s citizens to go to war against external and internal enemies. The nation is so beguiled by his charms that it loses its identity and its freedom of thought. Eliraz, who wrote the literary text, and Josef Tal, who was in charge of the musical setting, give an answer (albeit a rather controversial one) to the question of how the Ashmedai managed to restrict the freedom of thought that had characterized the people and the reign of the King.

In the humanist expectation of freedom of thought, an ambivalent reality is formed, one in which opposite fundamental premises pull the freedom in two opposing directions. On one side, there is the conduct of the King, who had ruled the kingdom for 500 years, fostering its peace and well-being, cultivating his own capacity for self-criticism, and giving his family and his people the rational tools through which they could understand themselves and the rules of government.

We can assume that the main argument of the authors of the opera is that the King, who believes that he had managed to inculcate his people with the foundations of free, humane thought, does not see the other side of this kind of thought. As a result of his blind belief, he runs the risk of enabling the coronation of his diabolical double, abandoning his kingdom, and leaving his people in the hands of the devil. At this point, the other side of free thought is presented¬: the citizens, who were used to living in peace and seemingly enjoyed their freedom of thought, become addicted to the new King’s lust for power and become his willing slaves—the nation grows horns and a devil’s tail and generates hatred, fury, and insanity among its friends and foes.

Ashmedai also features an interesting historical aspect. It is an Israeli opera and its libretto was written in Hebrew by an Israeli poet and playwright called Israel Eliraz and performed in German in Hamburg in 1971. Joseph Tal, a German-born Israeli composer, adapted the music to the grammatical and prosodic structures of the German language, giving musical expression to the archaic images that had formed German culture and to linguistic idioms developed in modern German. Besides the foreign cultural component, Tal strictly follows the tradition of the Talmud—which gave Jewish culture the devilish figure of Ashmedai—with a modern understanding of the cultural dualism involved: the rationalism of Talmudic thought is contrasted with an anarchy that undermines the moral standards of Halakhic culture and the later Jewish thought that followed it.

The opera presents the meeting of cultures from a historical perspective, and this meeting is made more vivid through poetic and dramatic aspects. These aspects exist mainly in the complex world of the two main characters—the King and Ashmedai—and they are at the center of this paper’s discussion of the different aspects of emotional, social, and cultural disorientation which, in part, led to the masses’ unrestrained allegiance to the tyrannical leader.

# Ashmedai from a Cultural-Historical Perspective

The opera Ashmedai is the result of a cooperation between three important creative artists: Professor Rolf Lieberman, the director of the Hamburg Staatsoper; Josef Tal, a Berlin-born Israeli composer; and Israel Eliraz, a Jerusalem-born poet and playwright. Professor Lieberman approached Tal with the request to compose an opera that would be staged in Germany, in German, about a theme of Tal’s choice. Tal was determined to write the libretto in Hebrew. In 1971, the opera was produced for the first time in Hamburg, in the German language, based on a libretto written in Hebrew by Israel Eliraz in 1969. The opera was subsequently translated into English and staged at the New York City Opera in 1976[1]. Tal chose Eliraz as his co-creator for this major production because he was aware of Eliraz’s poetic and theatrical force, evinced by the plays he wrote in the 1960s, and his sober attitude when dealing with sensitive issues, such as the individual’s struggle to maintain his individuality in strict bureaucratic systems. Tal wrote about the sense of cooperation between the two men in his article “How My Opera was Born,” in which he notes both collaborators’ connection to Jewish and Western culture and describes how this connection influenced the work’s dramatic and artistic worldview:

It was clear to me that it was in Israel that I had to find the author of the libretto and that the material had to have a Jewish-Israeli content. I found the Jerusalem writer Israel Eliraz, who had a great deal of stage experience, and we immediately began a series of talks in which I clarified my attitude to opera in the twentieth century. We dealt with ideas and intentions and I suggested a tentative date for submitting the libretto. From that moment intensive work began with Israel Eliraz. It immediately became clear to me that I had found the ideal collaborator for my work. As the subject for the libretto we chose the Talmudic legend about Ashmedai and King Solomon. The story was freely adapted by Eliraz, so that the universal and timeless relationship between good and evil received a framework of political actuality.[2]

The Talmudic legend that Tal alludes to in his article is the Midrash as told in Sefer Ha-Aggadah (The Book of Legends)[3] and in Bialik’s later literary treatment in his book Vayehi HaYom[4]. The Legend tells of how Ashmedai, king of the demons, takes over King Solomon, who was in search of the Shamir worm in order to build the Temple. In an interview about the libretto of the opera, Eliraz tells of his lasting fascination with the multi-layered character of the demon, who dresses up as Solomon and inflicts destruction on the kingdom. In Jewish tradition, the king of demons has clownish and joker-like abilities: he is a cunning creature with a predilection for drink and lechery[5], similar in his nihilistic character to the folk demon often described in Medieval folk tales.[6]

Eliraz based the libretto on the plot of the legend[7] and created an unruly world in which a political, personal, and erotic drama takes place between Ashmedai, who takes over the kingdom with his devilish deeds, and the King, who lives in carefree complacency and ignores Ashmedai’s destructive power. The takeover comes to pass with the acquiescence of the King, who sells his kingdom to Ashmedai and retires to a new life with a woman he loves. The pact the King signs with the devil is the axis around which the plot pivots, showing the King’s double-faced nature: on the one hand, he is a liberal who had maintained peaceful relations with the kingdom’s neighbouring countries for 500 years; on the other hand, he ignores the basic needs of his people and his hungry peasants. On the one hand, he is a peace-loving leader; but on the other, he ignores his wife, derides his son’s wishes, and abandons his daughter. The liberal who takes pride in his rational thought eventually yields to the powers of sorcery because he cannot penetrate the depths of his own soul and understand the real needs of his family and of his people. Ashmedai, by contrast, knows the subterranean motives steering the King and his people, and he channels them for his own use. With the consent of the King, he turns the citizens into ludicrous slaves who are carried away into ecstasy, to the point of committing murder, rape, and abuse.

The double-faced nature of the modern hero as it is presented in the opera bears a resemblance to the description of King Solomon in Pinchas Sadeh’s short essay on King Solomon and Ashmedai. In the essay, Sadeh points out the megalomania of King Solomon: while he signed pacts with other nations and built the Temple, because of his strength, no one could check his madness. Sadeh argues that Solomon was a greedy, lustful, and cunning leader, who tormented his people and stole their money in order to build the Temple. At the end of the essay, Sadeh writes: “And finally, although he did build the Temple, he also built next to it, in the valley of Hinnom, an altar to the most satanical of gods, Moloch, whose worship consisted of the burning of babies.”[8]

The double-faced nature of the modern hero as it is presented in the opera bears a resemblance to the description of King Solomon in Pinchas Sadeh’s short essay on King Solomon and Ashmedai.

The double-faced nature that Pinchas Sadeh sees in the character of King Solomon—and the lust and the death cult that accompanied the building of the Temple—also raise questions about the operatic King, who, despite his spark of wisdom and pursuit of truth, also acts with vanity when he decides to hand over the reins of the kingdom to a cruel tyrant in order to fulfill a spiritual, ecstatic, and erotic desire, leaving a scorched earth and hopeless citizens behind him. The King, who had spent his whole life as a good-hearted liberal, leads the masses to a life of lies, deceit, and recklessness in the face of the looming danger of the devil. The spiritual and cultural struggles within his personality receive musical and dramatic manifestations in the opera. The spiritual struggles are first presented in the dialogue between the King and the devil; they intensify as he realizes his mistake, which forces him to re-examine his belief that freedom of thought will help him overcome the rise of evil. The disillusion does nothing to alter the horrific fate: the devil ruins the kingdom and leaves the throne, and the King is sentenced to death by his son and the people.

# Ashmedai from an Ideal-Aesthetic Perspective

My fundamental assumption in this article is that the King undergoes a psychological process through which he recognizes his mistake. This assumption corresponds with the reading of Oded Assaf in his article “A Local School of One.”[^9] Assaf does not accept the assumption that the King has a complex personality. In his view, the King and his entourage are unresponsive to the people and to the impending disaster. For Assaf, the source of the opera’s tragedy is the King’s self-negation in the presence of the devil and in the loss of his citizens’ humanity. This self-negation is expressed through the description of the opera’s characters as shadows who are “devoid of first names (King, Queen, King’s Son, Advisors, Officer, Palace, City), who could be any person, in any place, at any time.” The loss of the humanity of the kingdom’s inhabitants is one of the reasons for their eventual addiction to the devil’s witchcraft. The “anti-human” position of the characters in the opera is closely related to the question that Eliraz is trying to answer, and it seems that there is no adequate answer. In the closing words of the libretto, he asks: “Why didn’t the people rebel?” “Is it not the people’s duty to hold the ruler accountable on a daily basis?”[10] In my view, in asking this question Eliraz shifts the focus to the human soul, which is striving to penetrate the unknown, enjoying a spiritual and emotional experience in the process, but ultimately falling into witchcraft and uncontrollable ecstasy. This duality in the figure of the King can perhaps explain the diabolical pact that he makes with Ashmedai and the effect of this pact on the masses: they too, like the King, are dragged by a leader to a paradise, which, in turn, leads them to addiction and to the destruction of the existing system.

My fundamental assumption in this article is that the King undergoes a psychological process through which he recognizes his mistake.

The devil’s takeover of the kingdom and the masses will be discussed in this article through two main aesthetic concepts. The first will analyze the ambivalent relationship that is formed between the devil and the King, in an attempt to explain how hard it is for a benevolent ruler to safeguard his freedom and his humanity. The second will focus on the mute uproar of the people, who remain powerless against the devil’s trickery.

# The Ambivalent Relationship between Ashmedai and the King

Tal and Eliraz created a cultural, ideological, and personal dialogue between the King and Ashmedai. In each of the three episodes where the two characters meet, there is a description of a different aspect of the seizing of power and of the individual who loses his identity. In each of these encounters, Tal and Eliraz use a different aesthetic technique. In the first encounter, Tal chooses a complex transformation technique in order to show how Ashmedai’s character changes: in the beginning Ashmedai pretends that he identifies with the King’s desire for freedom, but in the end he reveals his true face.[11] In the second encounter, the King meets Ashmedai, who then gives a speech in front of the masses. The speech is written in a strophic manner, which enables the listeners to take in the supposedly philosophical ideas that Ashmedai presents before them. In the third encounter, Ashmedai grows sick of the kingdom and returns it to the King. During this encounter, a duet takes place between the King and Ashmedai, in which the demon explains to the King why such cruel measures were needed in order to subdue the will of the people. In this scene, Josef Tal constructs a core theme around a single note, through which he illustrates the contempt that the ruler has for his helpless subjects.

# The First Episode—A Change of Identities

This episode is important at a cultural level, and it demonstrates how injustice might develop in a peaceful and unprotected society. It is also important musically and dramatically: Tal uses the transformation technique to show the change that the King and his family undergo.

The encounter between the King and the devil starts in the King’s bedroom. The devil disrupts the lighting arrangement, chases the tailor away from the bedroom, and says: “I am sorry for using a primitive ruse to chase the tailor away.” The devil uses the ambivalent term künsten—an artistic, malicious, and mischievous ruse. These three meanings blend together during the encounter. The ruse is designed to undermine the King’s authority in order to drive him out of power, as well as to make him less responsive and thus facilitate the subsequent subjugation. During this fateful encounter, the devil reveals his horns and his tail and initiates a game of cards, in which the King greedily participates without understanding the impending horror. Even when the devil presents himself as the King of Demons—König der Teufel—the King does not sense the danger and simply laughs along with the devil. The devil’s laughter is a cultural convention meant to show that frivolity nourishes evil and brings about the abuse of man through drawing on all of his weaknesses and poor habits.

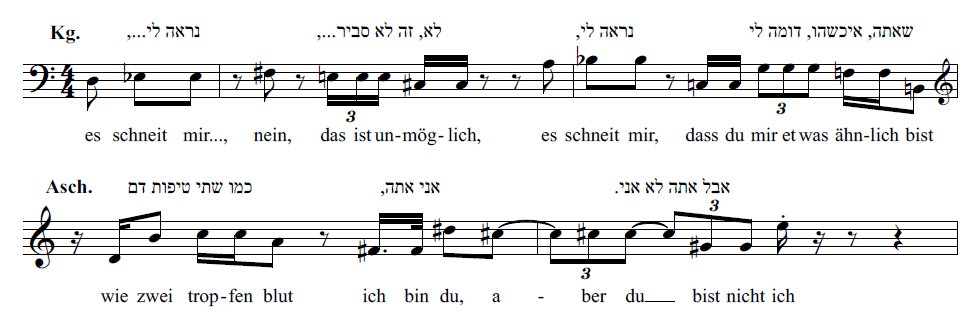

# Example No. 1: Ashmedai and the King

The malicious nature of the devil’s buffoonery is revealed to the King from the moment he sees Ashmedai presenting himself as the King. At this point the King understands that the devil is his alter-ego: “I believe…No, it isn’t possible… I believe…that you resemble me a bit…” Ashmedai: “like two drops of blood. I am you. But you are not me.” The almost identical physical features of the two heroes who differ in their moral and spiritual essences serves as an important building block in the opera. Ashmedai does the worst thing of all when he pretends to be the King, and the King, by contrast, merely takes a step back from his humane position and shows an inability to defend his people. Josef Tal presents the imagined similarity through “an interval series and a personal time-concept which denote his nature and personality.” Tal wrote an article on the nature of the contemporary opera, in which he mentions the importance of the permutation technique, which allowed him to “facilitate the emergence of variant forms which can reverse the original situation completely into an absolute chaos of tumult and uproar.”[12]

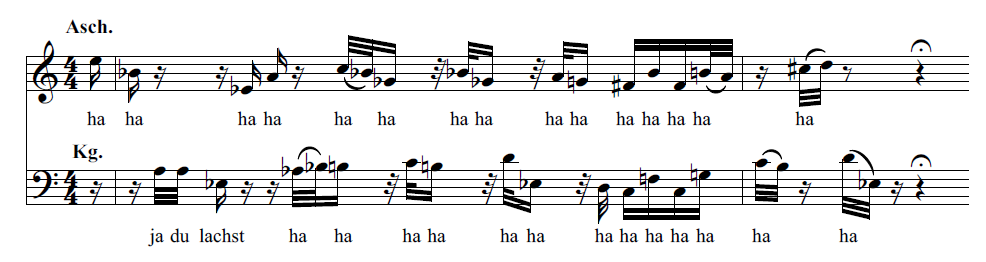

# Example No. 2: Ashmedai and the King

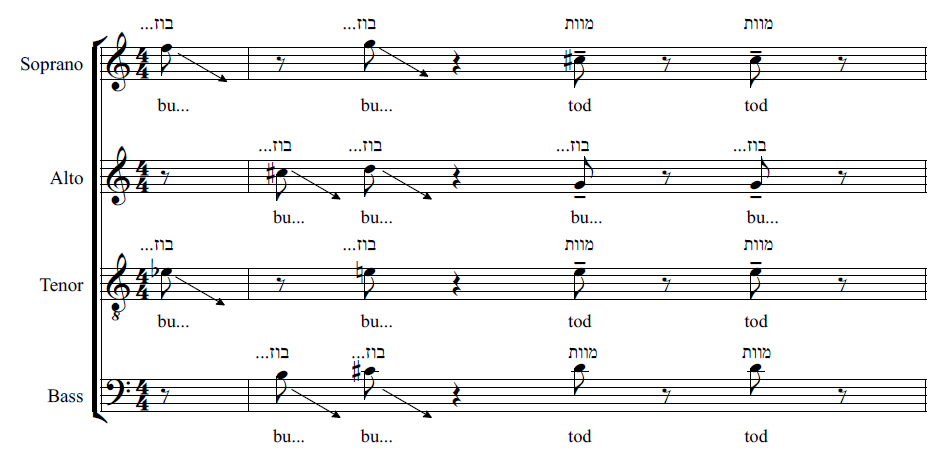

Josef Tal builds transformational relations through similar rhythmical patterns, and these patterns reflect the reciprocity between two conflicting essences: the essence of humanity and the essence of the devil. In the encounter between the King and the devil, the spiritual permutation of the King is established through laughter. Tal uses the permutation and applies it in the structure of the laughs of the devil and those of the King: the devil’s laugh consists of a two syllable “Ha-Ha” on C and B-flat (a major second); the King’s laugh consists of a two syllable “Ha-Ha” on C and B (a minor second). The second time the two characters laugh, Tal uses a tritone—often associated in Western music with the devil—an E-flat that ascends to A; and the King sings the same tritone, descending from A to E-flat. The two characters’ shared tritone points out the irony of the situation through a similar musical syntax, intended to illustrate the deceitful nature of the demon, who takes the form of an enlightened king.[13]

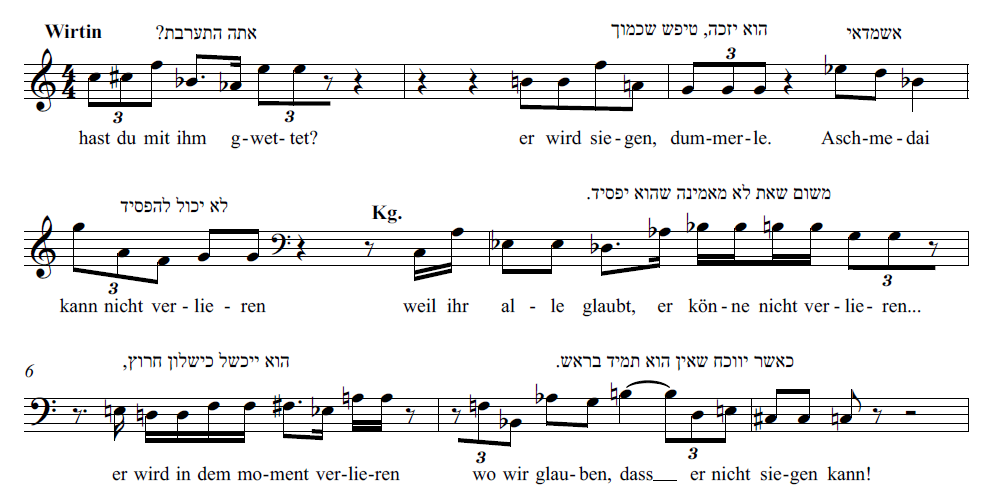

# Example No.3: The King and the Innkeeper

At the end of the dialogue in which Ashmedai says “I offer you a year of freedom from your wife and son,” the King opens the gate to him and lets him do as he likes with the kingdom. Ashmedai, hiding his true face through a veneer of buffoonery and humanity, reveals to us his devilish ruse: he enables the King to embark on a new life with a woman he loves so that he loses his kingdom. From this point onward, the kingdom belongs to Ashmedai. The King is now a foreigner, and he witnesses the downfall of the masses after the changes that result from his departure. The King leaves the palace and lives with the innkeeper, and she is the one who comprehends the magnitude of the disaster that is about to befall the kingdom. Tal hints at the diabolical character, this time by swapping the tritone for strings, clarinet, oboe, and bassoon during an agitato episode. The orchestra, like the innkeeper, reveals the looming disaster. The King, however, still believes that the masses love him and that they will not blindly follow Ashmedai, and so he says to the innkeeper: “He shall fail miserably” (in German: Er wird in den Moment verlieren). He says this in a tonal B-Major chord that appears in an atonal system, and in doing so gives the “innocent” chord a macabre character. The scene, which takes place at an inn, reaches its climax in the words of the innkeeper: “The devil does not lose. He always wins.” The innkeeper sings—like the King and the devil—in a recitative melodic line. Does Tal want to convey the devil’s sorcerous influence on the innkeeper? That might be the case, seeing that the shared recitative line serves as another layer of their switched identities.

The switched identities are an important part of the transformation technique that Josef Tal discusses in his article, which explains that at the core of every person lies a devilish entity waiting to break out, undermine one’s self control, and unleash chaos. At this point I return to Oded Assaf’s article, which notes the recitative line shared between the two characters, who have, after all, certain common features, even though each symbolizes a different entity.[14] Josef Tal points this out in his article, in which he gives the operatic character the attributes of the Talmudic Ashmedai:

Ashmedai is a demon who changes all things into their opposites: good into evil, man into beast, order into confusion. A many-faced devil of many tongues, he is the very genius of permutation…It is essentially a statement of the ever-recurrent theme of the conflict of extremes (represented here by the tolerant king and the intolerant Ashmedai), leading to general destruction. Fantastic though the legend may seem, its theme is one of universal purport; thus the constant permutations in the words and music can themselves convey a message to the audience without any recourse to explicit moralizing.[15]

# The Second Episode—Freedom of Thought Under Attack

The King, who has by now abdicated and is observing Ashmedai’s takeover, becomes passive. Ashmedai, in contrast, is now presenting an ambitious new artistic and human vision: art, philosophy, and literature. But he suggests that this cultural rebirth is only possible if the masses wear jackboots that symbolize their military superiority. “Jackboots” serves here not only as a synecdoche for the cruelty of the soldiers, but also as the basis for a series of images that offer demagoguery in the guise of rhetoric. Through this demagoguery, Ashmedai manages to plant in the masses’ consciousness the seeds of fallacy and turns them into contemptible slaves.

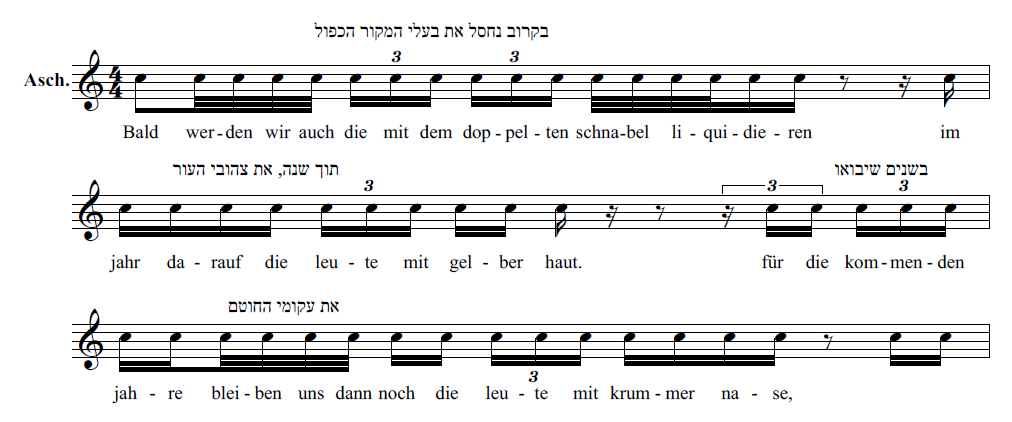

Eliraz presents the series of contrasting images—images of destructive military force beside ones conveying bravery and humanity—through a speech that Ashmedai delivers to the people of the kingdom in the public square. Eliraz writes poetry with hypnotic elements that soften the fallacious tales of the new king. The poetry is written in four strophes, and uses anaphora and a unified rhythmic meter that fits the Hebrew text. Josef Tal translates the prosodic sphere into the rhythmic structure of the German language and maintains the strophic structure of the text through a division into short phrases with an ending line that is repeated in every phrase. Both versions keep intact the suggestive and performative character of the speech. The suggestive character of the speech expresses the sharp change in Ashmedai’s messages since his rise to power. Unlike the first episode, where he employed trickery and clownish charm, in this episode he shows his hand and reveals his true intentions: to perpetuate the subjugation.

Eliraz presents the series of contrasting images—images of destructive military force beside ones conveying bravery and humanity—through a speech that Ashmedai delivers to the people of the kingdom in the public square.

Ashmedai appears before the people:

“My worthy people!

We are a nation of philosophers.

Yes, but who knows it?

You go barefoot and wind rags round your feet,

But if we put our knee-boots on, then ev'ry-on realise

We are a nation of philosophers.

My worthy people!

We are a nation of music lovers,

But who knows of it?

You go and wind rags around your feet,

But if we put our knee-boots on, knee-boots on,

Then ev'ry-on realise

We are a nation of music-lovers.”[16]

Josef Tal constructs a special musical system to fit the strophic structure of the text. He divides every paragraph to a string of short phrases, each one ending with the note A. This note has a symbolic meaning—a musical display of imperviousness is achieved through the monotonous obsession with it. This is the musical equivalent of the phrase “and who even knows about it?” The note, which ends the phrase, drones out the cruel invasion of a ruler who claims he knows the inhabitants better than they know themselves. There is an element of a hidden or implied horror here, which signifies the ruler’s ability to penetrate the consciousness of the inhabitants.

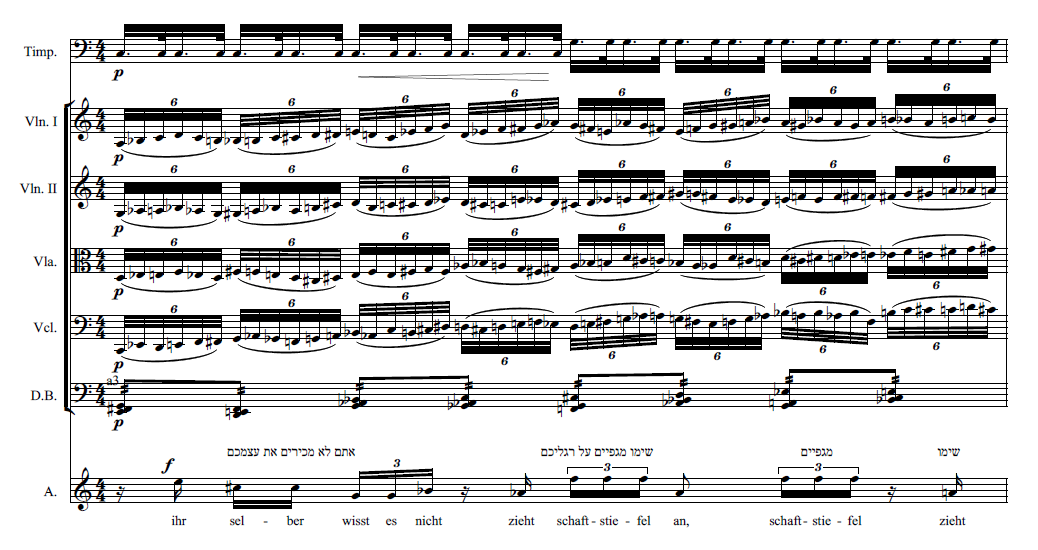

The devil’s absolute control is conveyed in the sentence: “You do not know yourselves. Wear boots.” The string section plays so fast (each beat is divided into sextuplets, played in 32nd notes) that the beat’s undulating movement is hardly felt. There is a sense of a troubling atmosphere that is heard on the lowest register of each of the string instruments. The troublesome quality increases with the tremolo played on the double bass, which invites the kingdom’s subjects to listen to the voice of the ruler. This bar is an example of the rhythmic fluctuations symbolizing the restlessness of the people.

# Example No. 4: Ashmedai and the People

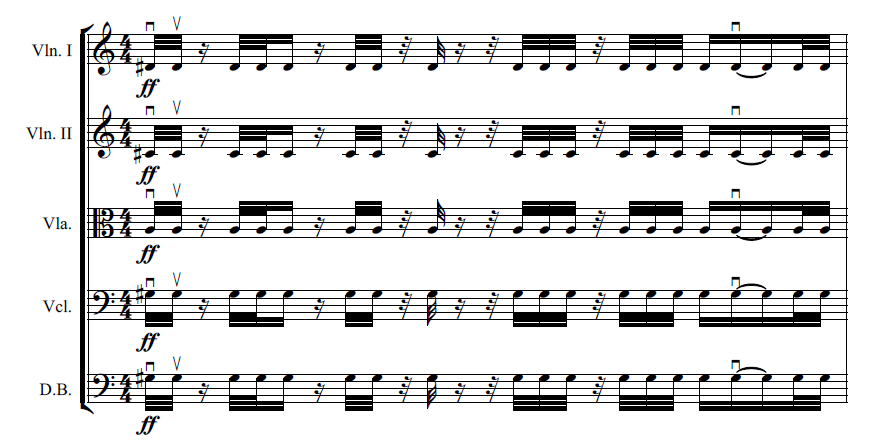

After the speech in which Ashmedai convinces his subjects to wear jackboots, the orchestra plays a series of harsh sonorous gestures that brings to mind, on the one hand, the passion of the masses and, on the other, the tyrannical nature of the ruler(s). Three bars after Ashmedai exits the stage with a clear victory, Tal creates a string of disrupted melodic patterns, in a single rhythm, without the possibility of expressing the unique vocal idiom of each of the string instruments. Here Tal adds flashes of very short silence, which strengthen the sense of horror. The theatrical scene ends with the soldiers forcing the people to put on the jackboots, and the score says that “everything happens as if it were an act of rape.” The description Tal writes in the score found its expression in the stage direction. It seems that there were allusions to rape that received visual representation on stage. The viewers understood the violent meaning that Tal wanted to convey with the act of putting on the jackboots.

# Example 5: The Voices of the Masses

# The Third Episode—the Destruction of the Kingdom

The third meeting takes place a year after Ashmedai’s rise to power. Ashmedai has turned the kingdom into a wretched killing field. The soldiers dance a dance of death and pain. They lose their humanity: they rush to devour the corpse of a dead horse, and one of the soldiers rides the head of the horse, ascending on it to the mountains.[17] At the sight of this horrendous scene, the final dialogue between the King and Ashmedai takes place. The despondent King acknowledges his fateful mistake. Ashmedai celebrates the victory of killing and chaos. The dialogue between the two presents not only the weakness of the King and his inability to withstand the evil force of Ashmedai, but also the intensity of the tyranny, presented in sweet talk:

The third meeting takes place a year after Ashmedai’s rise to power.

The King: What have you done in the past year?

Ashmedai: We have brought culture to the world. We have destroyed the one-eyed and one-eared creatures. Soon we shall destroy the double-beaked creatures. Next year we shall destroy the yellow-skinned ones. In the years to come—the crooked-nosed, the green-eyed, the bald…

The King: and then what?[18]

At the end of the dialogue, the King acknowledges his mistake. But even at this turning point, he does not initiate any kind of counteraction; rather, he simply voices a position of abject defeat: “I am not a king, and I have no people. I am more to blame than anyone else. I believed in their innocence […] Take my life […] Kill me.”

Here the ambivalent identity swap between the King and Ashmedai reaches its dramatic climax. In the conversation, the King conveys compassion for himself and for the fate of his people; Ashmedai, by contrast, reverts to the mischievous character with which he first introduced himself. He obviously does not feel any compassion. He has reigned through terror and is leaving behind a bloody, suffering kingdom.

# Example No. 6: The Destruction of the Kingdom

Tal uses a number of important musical techniques that express the evil of Ashmedai in contrast to the King’s weakness. First and foremost, it is worth noting the use of the C motive, with which Ashmedai describes the cruel acts he has committed in the kingdom.[19] The speech starts with a syncopated upbeat on C in a rhythmic pattern played in 16th notes, a pattern which is repeated obsessively. The singing is without direction and without development, symbolizing the mechanical nature of the tyrant’s thought. This mechanical thinking is expressed in music through the obsessive nature of the motif, which brings the state of the kingdom back to the fixated thought in which it had been stuck for 500 years. The repetition strengthens the ambivalent relationship between the King and Ashmedai.

The fixation of thought is a delaying mechanism in the management of the kingdom. First, the King delays the building of a dam in order to solve the problem of drought, which was ruining the crops and making the peasants hungry. The King does not understand his son’s wish to change fixed orders, and he treats him the same way he treats the rest of his subjects—with indifference and irresponsibility. It is, therefore, no wonder that the kingdom eventually falls and Ashmedai fills the gap with promises of happiness, power, and wealth. The King turns his back on the needs of his people, while Ashmedai pretends to show interest in the fate of the poor, the ambitions of the King’s son, and the kingdom’s sense of abandonment.

The three aspects which were discussed with regard to the ambivalent relations between the King and Ashmedai—double identity, the loss of freedom of thought, and the destruction of the kingdom—are also reflected in the relations between the King and the masses. The first aspect, which reflects the destruction, is presented through the perspective of the Queen, who listens to the peasants’ song and weeps for the fate of the penniless people whose crops were devastated. The second aspect, which reflects the loss of freedom of thought, is presented through the orgiastic outburst of the masses; this outburst is heard at the beginning of the opera through the electronic sounds that accompany the lustful bacchanalian scene taking place on the stage. The third aspect, which reflects the destruction of the kingdom, is presented through the execution of the King by his son and the raging masses.

# The Mute Outcry of the People

The first aspect is presented in the first example—the song of the peasants—which describes the Queen’s emotional void, the financial ruin, and the King’s indifference to the fate of his subjects.

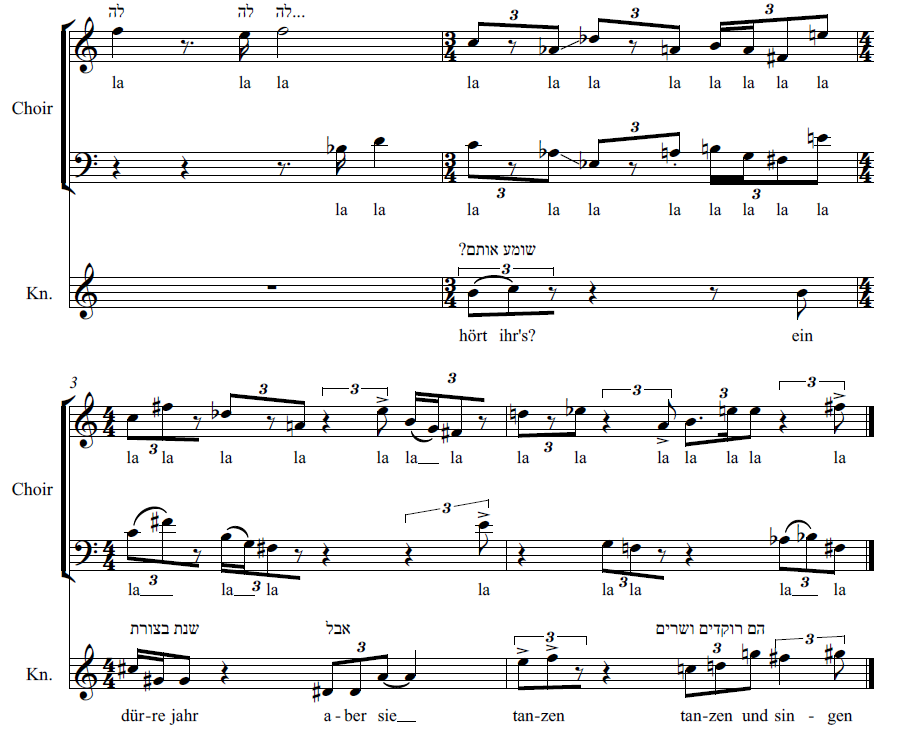

# Example No. 7: The Queen and the Peasants

In the song of the peasants, the Queen serves as a mirror reflecting the absurdity that prevails in the kingdom—the King is initiating a military coup, and the father goes out to party with his mistress, the innkeeper. The Queen, who has remained in the palace, testifies to this absurdity with the words “there is a drought, and the peasants are dancing and singing.” This sentence reveals the King’s role in the crumbling of the kingdom. Her words give the sense of a philosophical epigram with cultural and social significance—they illustrate how a people is oppressed to the point of not understanding their own situation. Tal creates a complicated rhythmic system featuring all the voices together and every voice separately. The triplet in the Queen’s line imitates the beat of a folk dance, and perhaps alludes to her identification with the fate of the poor. The soprano is heard in syncopated sounds in between the fast bass notes. The two voices allude to the inarticulate language of the peasants. They say just one simple utterance: “La, La.”

In the song of the peasants, the Queen serves as a mirror reflecting the absurdity that prevails in the kingdom—the King is initiating a military coup, and the father goes out to party with his mistress, the innkeeper.

The peasants weep in their muteness and their inability to express their pain and internal truth. In this example, Tal anticipates and heralds the mute outcry of the masses, which he represents mainly through the electronic texture.

The second aspect is presented through the musical landscape that Tal designs with the electronic tone texture. Through this texture, the masses weep about their muteness as they engage in acts of orgiastic drunkenness and insanity. Tal develops an orchestration of electronic notes that are heard with intense density to the point of having no measured rhythmic figures. Assaf writes about these sounds that “it is as if they burst out of directionless chaos that fills the stage with dense masses of sound.”[20] According to Assaf, the electronic notes serve as a background to the orgiastic dances, which bring to mind the drunkenness and death of bacchanalian rituals. In fact, the bacchanalian atmosphere is already felt in the opera’s prologue. The prologue features a dark scene, in which only the shadows of dancers are seen on stage. The indistinct characters go out from the market square toward the palace, and they are accompanied by Ashmedai, who disguises himself as one of the dancers. The orgiastic atmosphere of the prologue is transformed toward the end of the first act, with electronic sounds that accompany the army’s murderous butchery and the cruel deeds of the devil’s henchmen.

The second aspect, which points to the importance of electronic orchestration in the opera, is presented in the article through Tal’s own words in his book Ad Yosef and by the symbolic importance which can be attributed to electronic music.

In his book, Tal describes the complex relationship between the poetic text, the orchestra, and the electronic music in the prologue:

The electronic music corresponds with the actions taking place on stage without the mediation of words. As the audience members were entering and taking their seats, the stereo system, which was hanging from the ceiling throughout the hall, was emitting a silent bass that seemed like it was moving from place to place. The audience, still wondering about the nature of the sound, still trying to understand its origin, was already an active part in the happening, even before the lights were off. Then a complete darkness took hold of the opera hall. The continuous bass note broke into short unidentified notes that reached the audience’s ears from several stations on the stage. Here and there, a light flickered, the network of sounds became denser, the stage got brighter, and, slowly, the elements of the set design came down from the ceiling and the legendary city was built by the stage workers. The citizens of the city then came dancing into the colourful city fair. Ashmedai is seen among them, bringing them into insane ecstasy with his sorcery.[21]

The relationship between the electronic music and the acoustic music intensifies at the end of the second act, after the kingdom collapses and the masses dance in insanity and horror. Tal gives symbolic meaning to the variety of electronic sounds and to their interaction with the singing and with the sounds of the orchestra.

The symbolism of the electronic sounds with which Tal conveys the psychological and cultural world of the heroes, who experience chaos and horror, is also connected to particular aesthetic and cultural attitudes, which have been discussed in many studies on the nature of electronic music. Here I want to mention the work of Joanna Demers[22], who studies the aesthetics of electronic music. Her fundamental assumption is that electronic sounds convey aesthetic and cultural meaning. Demers lists the attributes of electronic music: there are no set parameters—such as a descending bass and a specific syntax in a lament, or four-quarter rhythm in a march—and there is no tonality or pitch. She believes that we are in “a no-man’s land,” since by its very nature, early electronic music was meant to entail a different approach to the materials of sound, to tease the listener into avoiding cognitive associations and to help him or her reach a more personal understanding. In her book, Demers touches upon the divided opinions regarding the ability of electronic texture to manipulate sound. She also raises questions regarding the extent to which electronic music can approach the world of previously-known sounds, the extent to which it is capable of operating in the sphere of acoustic sound, and the extent to which abstract sounds created in a studio can convey metaphorical and symbolic meaning, which is interpreted with cultural and musical imagery that exists in a familiar acoustic reality. According to Demers, the musical materials of electronic music are not autonomous; rather, they answer human, social, and political problems, as do many acoustic musical spheres. The abstract sounds produced by a magnetic tape—or, more recently, by computer technology—carry, in her opinion, aesthetic, psychological, and social meaning.

The symbolism of the electronic sounds with which Tal conveys the psychological and cultural world of the heroes, who experience chaos and horror, is also connected to particular aesthetic and cultural attitudes, which have been discussed in many studies on the nature of electronic music.

Tal also includes numerous instances of symbolism, through which one can learn about his critical attitude toward the behavior of the masses, who are spellbound by Ashmedai’s sorcery. Tal intensifies the critical aspects by fusing the acoustic music with the electronic music. The acoustic music gives expression to a narrative of the fall of the kingdom and to the nihilistic aspect of a place that has lost its moral and human direction. The electronic music, on the other hand, gives expression to the subterranean levels of chaos and illustrates the people’s—and the King’s—sense of helplessness against the brute force of Ashmedai.

The third aspect, which relates to the end of the kingdom and the culture, is addressed in the opera through two scenes. In the first scene, the King is accused of treason. In the second, he is humiliated by the masses and executed.

# Example No. 8: The King is Accused of Treason

After Ashmedai leaves the palace, the kingdom becomes the scene of complete unruliness, for which the King’s son—who is now wearing military attire and preparing the nation for a war against an unknown enemy—is responsible. The son emphasizes his own masculine identity and fulfills his role as the new sovereign. Tal presents a series of rhythmic and melodic figures which bring to mind military marches (symbols of totalitarian rule), alongside ones that the son sings in a disrupted melodic line that recalls Expressionist harmony and conveys anxiety and alienation. The conflicts within his personality reach their climax in the trial he conducts against his father, whom he accuses of treason. The son throws the father to the angry mob, and the mob crucifies him and leaves his corpse at the gate of the city.

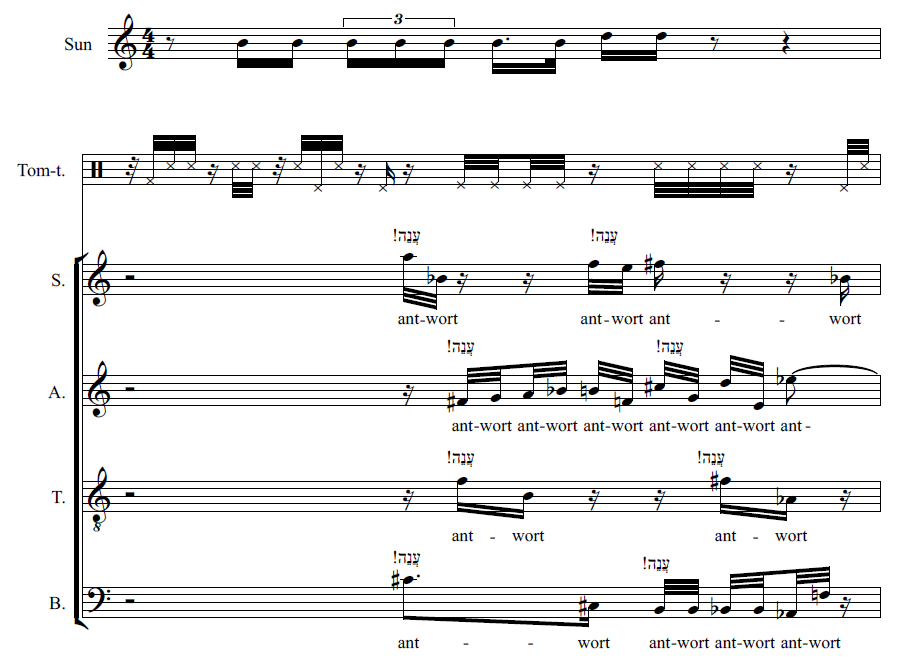

The King’s son secures the legitimacy to persecute his father from Ashmedai. Tal presents a pseudo-psychological transformation in the son’s character: he transforms from a child with no rights to a vicious military leader, but no real change occurs in his personality. In both states he is spineless and without character, and thus it is easy to convince him to put the King on trial and, eventually, to sentence him to death. The son interrogates his father and asks him if he has changed his attitude toward the kingdom. The choir follows in an echo, accusing the King of treason. The choir shouts one word: “Answer! Answer!” (Antwort) and legitimizes the people’s desire to follow the new King’s decree. The same peasants who, at the beginning of the opera, could not express their terrible misery, are now the forceful masses, and they cruelly direct their force against the King. In both cases, the paucity of thought and feeling are revealed—a spiritual paucity that impairs their judgment and their ability to manage the affairs of the kingdom. At the end of the opera, the masses assemble by the gallows and help to crucify the King, who has fallen from grace.

# Example No. 9: The Crucifixion

The musical scene that accompanies the modern crucifixion in Ashmedai recalls the crucifixion scene from Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. The King, like Jesus, is doomed to face spitting and humiliation, and he too—like the mythic hero who suffers the wrath of the masses— ends up as a victim of folly, evil, and blind obedience.

In the modern opera, as in the baroque work, the word “contempt” is accentuated with a staccato that characterizes the melodic line and through the use of brass, which intensifies the judgment-day feeling. In the judgment day scene, Tal uses baroque musical techniques to illustrate the cruelty and insanity. The combination of the baroque music and the dodecaphonic music intensifies our sense of empathy for the King and the price he has to pay in his journey toward transcendence, from which he returns sober and hurt.

In the modern opera, as in the baroque work, the word “contempt” is accentuated with a staccato that characterizes the melodic line and through the use of brass, which intensifies the judgment-day feeling.

There is an interesting use of a minor ninth pattern, one which starts with a base note and then builds on the complement interval. The inverse structure produces a connection between the contempt and the death, alluding to the end of the kingdom, the nihilistic elements that characterize the immoral conduct of the rulers, and the sense of helplessness experienced by the masses.

The immoral conduct of the rulers, who had brought about the end of culture, was also discernible to the German viewers of the opera, as they watched the uproarious dance of the unruly masses. The audience’s shocking encounter with the scene during a performance in Hamburg in 1971 was described by Tal in his book Ad Yosef:

We experienced an odd experience before the intermission. The first act ends with the drunk hysteria of the people, who are persuaded by the spurious king into starting a war. The ring of bells and billows of smoke fill the stage. Then the noise subsides, and the light is turned off to the sound of distant thunder. We were expecting the standard applause, but there was complete silence in the hall. No one moved. Far away, in the balcony, some hesitant clapping was heard, but the audience silenced it with angry “shhh” sounds. When the light was turned back on, everyone stood up and went out. This reaction, which we were not ready for, showed us the enormous impact of our transparent allegory on the German audience, even though this was no less than 26 years after the war. It saw itself in this depiction of a nation that follows the devil—disguised as a leader—in an ecstatic frenzy, and it bowed its head in shame.[23]

The human hero in the unruly reality depicted in Ashmedai is a king who has abdicated his throne for his own personal happiness. The work is a powerful current of creative imagination which confronts the dangerous place of myth in the real world, and this is probably the reason behind the shame that Tal recognized in the production’s audience. And yet, when the analogy to the real world is made, the reality it alludes to is far more unimaginable—the primeval-imaginative component of Tal and Eliraz’s work makes every human step taken (e.g., the King’s abandonment of his kingdom) poisonous and destructive. Ashmedai’s involvement in the events implies there is a “universality” at work and attempts to hijack the place of “reality.” Thus, Tal and Eliraz’s work deals with the loss of the ambivalent elements of reality over which human beings are supposed to have control. When reality is bewitched, any personal solution is inherently immoral. The imagination is detached from the claims of reality. Ashmedai functions in the opera as a warning against the abandonment of the social arena.

It seems that nihilistic components, which are surely ingrained in the tradition of German culture and literature, had seeped into the consciousness of the two Israeli artists. In this work, Eliraz and Tal present a high-rise architectural structure, which houses, side by side, the endless sufferings of a man who searches for fulfillment in the transcendent and who eventually finds himself entrapped in the deceptions of witchcraft, which lead him astray and undermine his ability to discern good from bad and right from wrong. The King, in his search for happiness, loses sight of himself and allows Ashmedai to infiltrate every part of the kingdom where there is truth, purity of thought, and moral action.

It seems that nihilistic components, which are surely ingrained in the tradition of German culture and literature, had seeped into the consciousness of the two Israeli artists.

# Notes

[1] In 1976 the libretto was translated into English, and Joseph Tal adapted the music to the English text. Israeli conductor Gary Berthini conducted both productions, in Hamburg and in New York. In both productions the name Ashmedai was kept as the opera’s title. The libretto was published in Israel Eliraz, The Little Book (Tel Aviv: Yachdav, 1983) pp.95-120. Jacob Mittleman produced the German translation.

[2] Joseph Tal, “How My Opera was Born,” at www.josephtal.com.

[3] Hayyim Nachman Bialik, Sefer HaAggadah (Tel Aviv: Dvir, 1960), pp. 92-98 (Hebrew).

[4] Hayyim Nachman Bialik, Vayehi Hayom (Tel aviv: Dvir, 1965), pp. 124-130 (Hebrew).

[5] Israel Eliraz, “From the Notes of a Librettist,” Bamah 52 (1972), pp. 99-104, esp. p. 102 (Hebrew).

[6] Arie Zachs, “Shkiat HaLetz,” in Shkiat HaLetz (Tel Aviv: Sifriat Poalim, 1978), pp. 19-38.

[7] Israel Eliraz followed the original plot of the story “Solomon and Ashmedai,” which Bialik expanded in his book Vayehi Hayom, based on the midrash in the Babylonian Talmud (Gittin, pp. 64-71). The cornerstone of the story is the charged encounter between King Solomon, who wants to build the Holy Temple, and Ashmedai, king of the demons, who refuses to deliver the Shamir worm—which was needed in order to cut through stone without iron tools—to Jerusalem. The King sends messengers to the secret dwelling place of the king of the demons, and they cunningly lead him to Jerusalem. The Temple is then built and stands in all its glory among the nations. But at the end of the building process, Ashmedai outwits King Solomon and banishes him to the desert, far away from his palace. In a cunning, malicious act Ashmedai himself stays in the palace, dons the King’s regal robe, takes on his shape, and acts in his manner. Bialik does not detail the exploits of Ashmedai in the kingdom. He tells the story of the banished King and of his return to the palace. Eliraz gives the mischievous acts a malicious character and expands them to create the character of a cruel tyrant.

[8] Pinchas Sadeh, “A Short Essay on Solomon and Ashmedai,” Davar, May 17, 1983 (Hebrew).

[9] Oded Assaf, “A Local School of One,” Haaretz, December 24, 2010, pp. 1-15, esp. p. 8 (Hebrew). Assaf’s article, which was published in a daily newspaper, is, to date, the only one that discusses Ashmedai in detail. Assaf provides profound musical and metaphysical insights that could serve as a basis for a scholarly research on the opera.

[10] Israel Eliraz, “The Versions of the Libretto as a Dramatic Genre,” in The Little Book (Tel Aviv: Yachdav, 1983), pp. 181-189, especially p. 187 (Hebrew).

[11] Josef Tal discusses the permutation technique in his article, in both its technical and conceptual aspects. He writes that he crafted the character of Ashmedai with the transformation technique that he employs in the music, which, according to him, is the result of both the use of this technique in the Hebrew language and of the spiritual constitution of man: “In the case of Ashmedai, the central idea is the significance of the principal figure. Ashmedai is a demon who changes all things into their opposites: good into evil, man into beast, order into confusion. A many-faced devil of many tongues, he is the very genius of permutation. Now, a major characteristic of the Hebrew language is its constant permutation of letters, yielding changes of word-forms and meanings. Hence, in this case, the nature of the language affects the action of the opera through its perpetual transformation of words and concepts, and this is also matched in the permutation techniques of the musical composition.” See Josef Tal, “The Contemporary Opera,” in Ariel 30, Spring 1972, pp. 93-95.

[12] Tal, “The Contemporary Opera,” p. 94.

[13] In the same article (p. 93) Yosef Tal emphasizes the moment of deception in the things he says about Ashmedai: "The idea behind the reflection of Satan in the image of the king stems from the construction of similar spaces appearing in the permutations, which obscure this basic line for both." (Tal, "Contemporary Opera").

[14] Assaf, “A Local School of One,” p. 8.

[15] Tal, “The Contemporary Opera,” p. 93.

[16] The English version was done by Alan Marbe. Alan translated it from the German version, which had been translated by Jacob Mittelman from Hebrew in 1971. This was the version that was adapted by Josef Tal for the New York production in New York City Opera, in 1976.

[17] Ibid., p. 113.

[18] Ibid., p. 114.

[19] The note “C” as the base note on which a complicated thematic structure is built is a recurring structural element in many of Tal’s works, especially those written in the ’70s and ’80s. The identity of the note “C” was discussed by musicologist Yohanan Ron, who believes it serves as an ideal and stylistic starting point. According to Ron, by undermining the gravitational pull, Tal builds serial musical structures which express the spiritual breakdown of humans in the twentieth century and convey a wish to produce music that is constructed on new aesthetic principles. Ron provides many different examples from Tal’s instrumental works and examines the use of the note “C” in Ashmedai as an expression of uncertainty and a sense of aloofness. See Yochanan Ron, “The Note as an Idea and a Theme in the Late Works of Josef Tal,” in his book Israeli Music: A Collection of Essays (Tel Aviv: The Buchman Mehta School of Music, 2014), pp. 35-46 (Hebrew).

[20] Assaf, “A Local School of One,” p. 9.

[21] Josef Tal, Ad Yosef (Jerusalem: Carmel, 1997), p. 215.

[22] Joanna Demers, Listening Through the Noise: The Aesthetics of Experimental Electronic Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[23] Tal, Ad Yosef, p. 215.